Why “natural vaccination” usually doesn’t work

Although “natural vaccination” may seem like a sensible approach to build herd immunity against BVD, the transmission rates in extensive New Zealand beef herds are not sufficiently high enough to ensure that all susceptible female cattle are adequately protected before the high risk periods for economic losses.

Background

Given the costs of vaccinating breeding stock against BVD, many farmers and veterinarians have asked why we can’t just leave persistently infected (PI) heifers in the mob to naturally infect their herd mates prior to the mating period. After all, animals that develop immunity to BVD after recovering from natural infection are believed to stay protected against the virus for life whereas animals that are vaccinated must be re-boostered every year to maintain immunity. So “natural vaccination” would seem to make economic sense, right?

Study Objectives

In this study, we wanted to look at how fast BVD spreads in infected herds to determine if they would reach high enough levels of herd immunity before mating to break the BVD cycle.

Did you know……….

For farmers that can’t prevent their cattle from being exposed to BVD from infected cattle within the herd or from contact with other infected herds, vaccinating against BVD prior to mating can significantly reduce the harmful economic impacts and prevent the creation of new PI animals.

Methods

Starting in September 2017, we ran a field study with 75 beef herds across New Zealand that were not currently vaccinating against BVD to measure the level of immunity in heifers prior to the start of the 2017/2018 mating period. Participating veterinarians randomly chose 15 heifers that had just delivered their first in calf in 2017 and collected blood samples from each to measure their individual level of antibodies against BVD as well as a pooled antibody ELISA. We specifically targeted this age group because they are the youngest in the breeding mob and therefore the least likely to have been previously exposed to BVD. We also assumed that if at lease one PI calf was born into the mob, the heifers would have all been at risk of getting naturally infected with BVD through contact with those calves on pasture.

Any individual animals that tested negative for antibodies on the first round of sampling were tested again at pregnancy scanning to see if their status had changed (seroconversion). We then used this information in a computer simulation model to predict how fast BVD spreads in infected herds.

Results

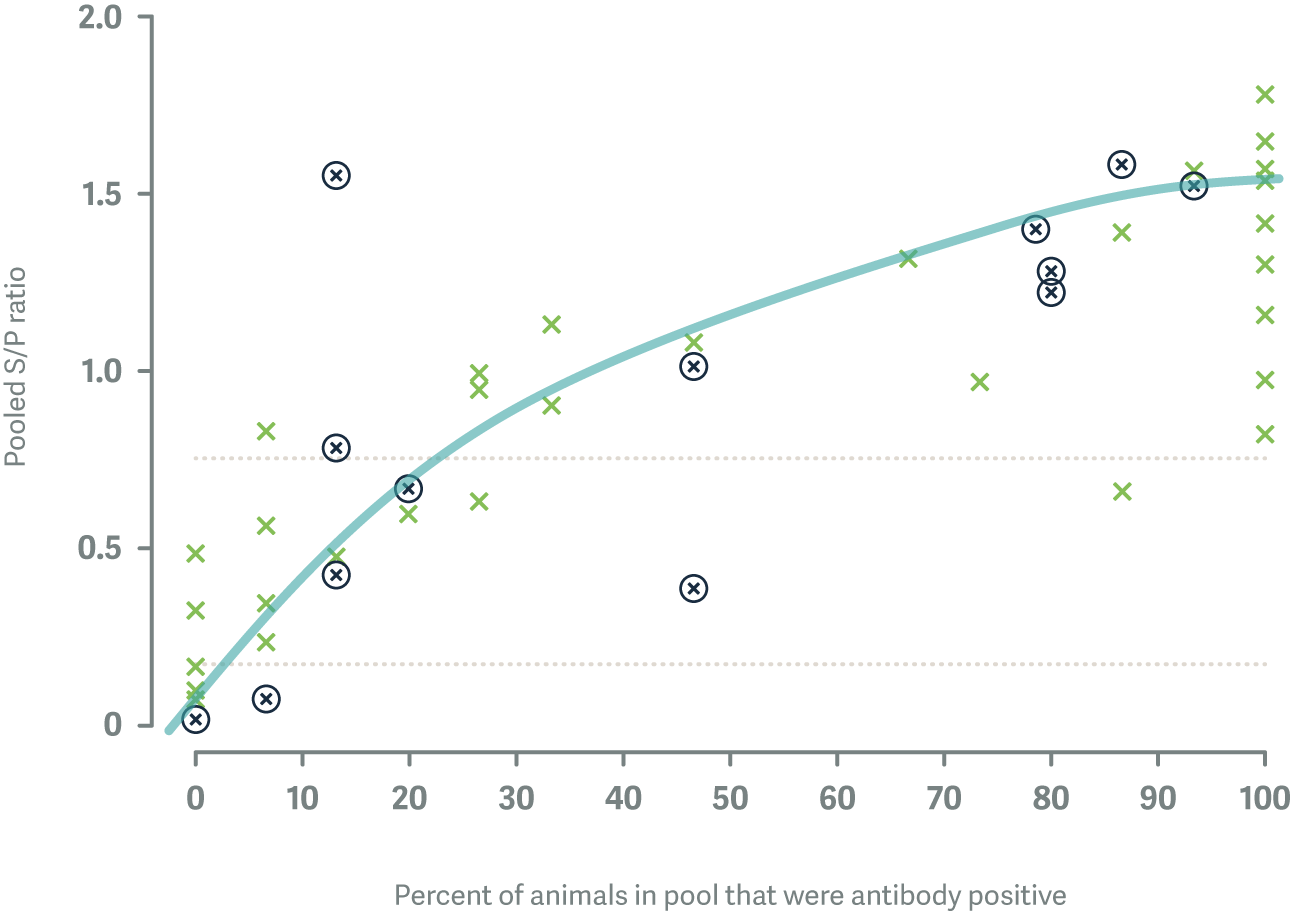

After the first round of sampling, there were 32 / 75 herds (42.7%) that showed evidence of active BVD infection based on results from pooled antibody ELISA, which is our first line screening test for determining the BVD status of beef herds. Only 12 of these herds (37.5%) had heifer mobs that were completely immune to BVD and 10 of these herds had <8/15 individual cattle that were already immune to BVD prior to mating.

Of 1,117 animals sampled 729 (65.3%) tested negative for BVD virus antibodies; when re-tested, 47/589 (8.0%) animals from 13/55 (24%) herds had seroconverted.

Each X represents a different study herd. The herds that are circled had cattle that seroconverted to BVD over the time period from mating to pregnancy scanning.

When we plugged these data into the simulation models, they produced an estimate that the average PI animal in a New Zealand beef herd infects about 0.11 animals per day (95% Confidence Interval: 0.03 - 0.34) or about 1 animal every 10 days. This suggests that BVD transmission in extensively grazed beef herds is generally slower than in dairy herds where the transmission rate has been estimated at 0.50 animals per PI per day or about 1 animal every 2 days.

Clinical Relevance

Based on these results, it appears that PI animals in extensive New Zealand beef herds may not be infecting other animals fast enough to ensure that susceptible breeding females gain adequate immunity to the virus before the pregnancy risk period for generating new PI calves. Herds that are leaving PI animals as “natural vaccinators” are also likely experiencing significant ongoing losses for poor reproductive performance and the effects of BVD infections on calf health. For herds that can’t easily get rid of existing PI animals through individual testing, we highly recommend starting a good vaccination programme to break the BVD cycle.

For further information about the study, check out: